This is the second half of a two-part post written by two mamas who have walked a similar – and yet very different – path. Both of their daughters, adopted from China with complex heart defects, required what most parents would consider a worst case scenario: a cardiac transplant.

Each shares their experience below.

Andrea, mom to Rini…

I am mom to six treasures, five adopted from China, four born with congenital heart disease. I am married to Eric, and I serve as Executive Director of Little Hearts Medical, an organization dedicated to providing hope for China’s orphaned and impoverished children living with congenital heart disease through the partnership and training of Pediatric Cardiologists and Surgeons. My youngest daughter, Rini, received an angel’s heart on November 13, 2013 at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

And Emily, mom to Lily.

I am the mother to five beautiful children. I am also wife to Jacques, a Pastor at Gateway Bible Church in Gainesville, VA. In my spare time I am a Forensic Science Professor and Graduate Program Coordinator at the George Mason University. My youngest daughter, Lily Grace, received the gift of life on June 14, 2014 through heart organ donation at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington D.C.

This post is the second of two parts. Please click here to read the first post.

………

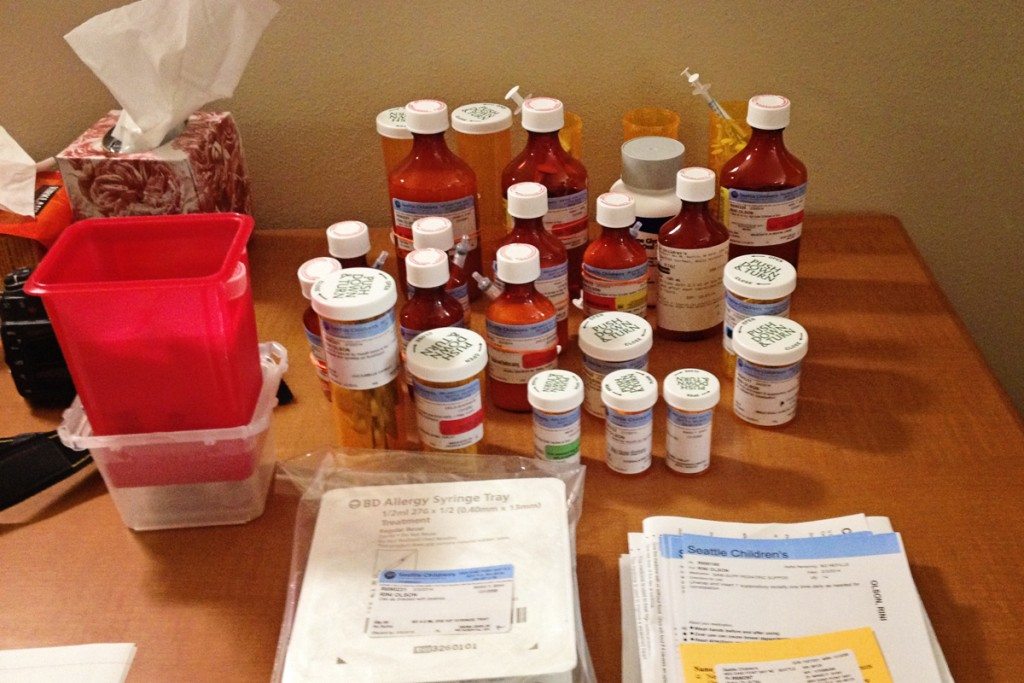

Medication

One of the most important responsibilities you will have after your child’s heart transplant surgery is administering their medications correctly. Before you will be allowed to leave the hospital to bring your child home you must be able to recognize each tablet, capsule, or liquid by color, shape, and size, as well as know all the medications by name, doses, times, and why you are giving each medication to your child.

In the beginning your child will likely come home on a couple dozen medications, and this task will be overwhelming and daunting. The good news is that before too long it will become a part of your everyday routine, and the quantity as well as frequency that your child takes their medications will dwindle over time. Some people find it helpful to follow a written schedule or a check-off list. Pill reminder containers and medication alarms may also be helpful.

Once your child is released from the hospital, you will need to attend follow-up appointments and/or transplant clinics. Most patients are seen one to two times a week for a month or more, and then less frequently as they improve. Your child will have frequent blood tests drawn and other tests and procedures. It will be important to monitor your child’s weight, blood pressure, pulse, and temperature especially during the first year post heart transplant. It will also be necessary to help your child maintain a healthy lifestyle that includes a balanced diet, regular exercise, and routine check-ups.

Your child will have an increased risk of skin cancer compared to other children who have not had a transplant. The medications that your child will take to suppress their immune system cause the increased risk. It will be recommended that your child see a dermatologist at least one time per year. It will be important to slather them up with a sun protection factor (SPF) of at least 30 to protect their skin from the sun’s damaging rays. The risk of lymphomas, cervical, breast cancer and colorectal cancer are also increased because of the strong immune-suppressing drugs that are required to help prevent rejection of the heart.

Your child may also have an increased risk of developing eye problems post heart transplant because their immune systems are suppressed. During an annual eye exam your child will have a dilated eye examination that can detect serious problems such as glaucoma, cataracts, diabetes, infection, and cancer.

Your child’s new transplanted heart will be denervated. When the heart is removed from the donor, the nerves to the heart are cut and the nervous system is “disconnected”. During transplant surgery, it is not possible to reconnect the nervous system in the donor heart to the recipient’s nervous system. Although the transplanted heart will beat adequately, there is no connection to external nerves that will affect the heart rate. The heart rate of a denervated heart will not increase as quickly with exercise, and they will need to take some time to warm up so that they do not become light headed or dizzy.

Heart transplant recipients require anti-rejection medications to suppress their immune systems so that the transplanted heart is not rejected. Because the immune system is suppressed by these medications, transplant recipients are always at risk for infection. The risk is highest during the first six months after transplant. Infections can also occur when higher levels of immunosuppression are needed to treat rejection.

Some of the concerns that may present themselves after the immediate post-transplant period include fluid build-up, overgrowth of gum tissue (gingival hyperplasia), excessive hair growth (hirsutism), infections, post-transplant Lymphoproliferative Disease (PTLD), cancers, and hardening of the arteries (Transplant Atherosclerosis). Some of these issues are medication-dependent, while others such as Atherosclerosis occur for reasons that are not yet fully understood, although it is felt that it be due to undetectable, chronic rejection. During the child’s routine heart catheterizations, the coronary arteries will be checked for signs of this disease.

Rejection

Rejection is an attempt by the immune system to attack the transplanted heart and destroy it. To prevent rejection, your child will take anti-rejection medications for the rest of their life. Up to half of all heart transplant patients will have rejection at least once during the first post-transplant year, even though they are taking their anti-rejection drugs. The first rejection episode typically happens within the first 6 months after the transplant. Rejection does not necessarily mean that your child’s new heart is going to fail. Most rejection episodes can be successfully treated with anti-rejection drugs.

There are two types of rejection. The most common type is “acute cellular rejection”. With this type of rejection, your child’s T-cells see their heart as foreign and attack the cells. This type of rejection occurs most often during the first few months after transplant and the risk decreases over time, although the risk of this type of rejection never goes away completely.

The second type of rejection is called “humoral” or “vascular” rejection. This type of rejection involves antibodies, which are proteins that your body makes to protect itself. These antibodies injure the blood vessels. This results in decreased blood flow and damage to the recipient’s coronary arteries.

During your child’s routine heart catheterizations, a heart biopsy will be done to find out if they are in rejection. The surgeon will remove 4-6 very small pieces of tissue from your child’s heart so that a pathologist can view them under a microscope. Your child’s biopsy results will be available either later that day or within 24 to 48 hours.

There are many ways to treat cellular rejection. For mild to moderate rejection the doctor may: increase the dose and/or frequency of the anti-rejection drugs, change the drugs, or give a “pulse” dose of prednisone. A “pulse” dose means that a higher dose is given for a few days and then the dose is slowly decreased down to its original dose. For more severe rejection, your child will likely be given stronger intravenous medications in the hospital. Steroids can cause very unpleasant side effects, and most children are quite unhappy during the treatment cycle.

Plasmapheresis is used to treat humoral rejection. Plasmapheresis is a process that filters the blood and removes the harmful antibodies that cause humoral rejection. These plasma exchange sessions are completed over a 2-3 week period. Echocardiograms and lab tests are done to see if the treatment is working. Patients with humoral rejection may also be given heart failure drugs similar to those they were on before the transplant.

Epilogue

From Emily:

If there is anything that I have learned over the past four years of medical opinions, medical testing, multiple surgeries, and long hospital stays it is that I should never expect anything. Early on my husband and I would get excited when we were told that Lily would be released from the hospital the next morning, and then she would end up inpatient for another few months with some new complication.

My best piece of advice to you is to go into this process with a completely open heart and mind. You must be willing to expect nothing, and accept anything. This journey will not be easy, but the blessings and joy along the way will be immeasurable. Always choose hope!

From Andrea:

Rini’s transplant was the hardest yet most glorious and life-affirming time in our family’s life, and such a beautiful illustration of God’s unwavering support. It has been a privilege to have a front row seat to a miracle, and to have been the beneficiary of another family’s grace during their time of despair.

If you are pursuing or parenting an adopted child with complex heart issues and have a question regarding cardiac care, feel free to email Andrea here or Emily here.

Leave a Reply