Like nearly every adoptive parent in today’s international adoption realm, my husband and I began our adoption process with the (dreaded) Medical Conditions Checklist – a list of conditions that we felt prepared for and would be willing to review files for. Birthmarks, check. Missing digits, check. Sensory processing needs, check. As an autism specialist, a parent of a child with autism, and a professional that has been in the special needs field for well over a decade, we found that we had checked yes to more conditions than we had checked no to. In the end, we realized that we were fairly open to most needs.

There were some needs, however, that we weren’t certain we would be the best parents for, and a big one – hearing loss. We didn’t know American Sign Language, and we don’t even live in an area where we could easily take lessons. The nearest Deaf school was an hour away. In our day-to-day lives, we do not even come across any other children with hearing loss, let alone anyone that uses ASL. How would we bond with a child we couldn’t even communicate with? When we adopted one of our other children, we dealt with years of attachment issues, so communication, bonding, and attachment were forefront in our minds. So, we left it unchecked.

We would learn many times in our adoption journey, however, that the old saying, “you plan, God laughs,” applies. Less than two weeks after we applied for the China special needs program through our agency, we received a file for the sweetest little one-year-old special focus child. He had just been moved from the Shared List to our agency’s photo listing. He was a tiny thing – less than 15 pounds fully clothed, and he was 15 months old. He was developmentally closer to five or six months old though – not sitting, not crawling, not able to hold his head up for long, no babbling. His file also said he loved to suck on his feet, wave at the moon, and be cuddled. He could also shake hands and was a “proud prince”. The sweet little round face in the pictures was perfect.

His file was a bit intimidating, even for us, coming into the adoption process with over a dozen years of special needs experience. We saw words we didn’t quite understand – cerebral dysplasia, very low DQ, poor brain development. There were words we did understand though – normal hearing, quiet baby, good sleeper, healthy. All things every parent wants to hear!

Not long after we received his file, the orphanage sent our agency a sweet three minute long video of the child. He was able to sit in a bumbo, pass toys from hand to hand, and make brief eye contact with the nanny. He seemed completely unphased by the noise around him, not even looking up when the nanny began banging things near him. However, you could see that he was interested in the world around him – genuinely curious. I’ve been in the autism field a long time, and it was quite clear that this child did not have autism. He looked weak, but he looked alert. The video gave us hope and, after consulting with our international adoption clinic, we sent our Letter of Intent to our agency. This was our son.

Soon after this, a family we met on an adoption Facebook group visited the orphanage and happened to see our son. We got the email we never expected: “You need to get here quickly. He doesn’t look good.” Following the email were videos of our son, even smaller and weaker than in the previous videos – no longer engaged in what was happening around him. Between the two videos, you could see that he was giving up. We immediately contacted our agency and raced through our adoption process. Our agency continued to get updates from the orphanage, but throughout this process, neither the orphanage nor the agency knew exactly what was going on with our son.

As parents in progress, we knew that we needed to be prepared for the worst-case scenario for the diagnosis in the child’s file, although this proved to be a bit difficult in our case when the diagnosis in the file had no actual English equivalent. We didn’t know quite what to be prepared for. In our updates from the orphanage, we were eventually given a paper from the orphanage doctor in the orphanage that said “suspected cerebral palsy”. Our son had gotten so weak that we were told to prepare that he might need a wheelchair. He still wasn’t making sounds at this point – over 18 months old – and wasn’t responding to the nannies or other children, so we were also told to prepare for some type of cognitive issue. “You might also consider possibly rescinding your Letter of Intent. You don’t have LOA yet and nothing is set in stone.” But after a lot of tears and prayers, this he was still our son.

We began to read everything we could get our hands on in terms of cerebral palsy interventions. We lined up potential therapists and medical professionals, had a pediatric walker ordered, and began researching possible adaptations we could make to our two story house if need be. The only thing we did know was that we didn’t know what was actually going on with our son. We wouldn’t know until we got him home.

Finally, it was time to fly to China – my husband and I, along with our three young children. At last, we would meet and hold baby Max. We entered the small room in Zhengzhou where Max would be brought to us. After what seemed like an eternity, we saw him – tiny, calm, and very quiet. While the other babies and toddlers were crying and scared, Max was unruffled, looking at everyone and taking in the whole scene. He had one tiny squeak of a cry, but then continued to just observe everything around him. Not scared, not overwhelmed…just watching.

For the rest of the first day, our family stayed in the hotel room playing, bonding, and beginning our adjustment. We were struck by how easily Max acclimated to this new situation. He didn’t cry at all. In fact, within hours, he was smiling and laughing. This child who always looked so frail and weak in his videos (before we traveled, we had seven or eight videos!), was smiling and laughing with his new siblings. His eye contact was impeccable and he was one of the most engaged children I had ever seen. And, like his file said, he was an excellent sleeper. You wouldn’t think anyone could sleep for 12 hours straight in a hotel room full of children, but he could.

Our time in China was so unlike our previous adoption from Vietnam. Max fit in so well and we were able to go out on all of the group tours, as well as go out exploring on our own. He was an easy-going child who loved being in a sling and was always watching the world around him with this immense curiosity. He didn’t look like a child with cognitive impairments and he certainly didn’t act like a child with cerebral palsy. In fact, he appeared to us to be a very typical child…. until the hotel fire alarm rang not even ten feet from where Max was sitting. We were all in the hotel room finishing up a meal and as soon as the deafening alarm rang, we all leapt and looked towards the door – except little Max who was happily playing with the food on his plate. He didn’t even look up or flinch. We knew in an instant what that meant.

When we arrived back home, we immediately dove into the world of medical appointments and testing. Things were ruled out almost immediately – no brain damage or cerebral palsy, and IQ tests came back normal. He was weak and delayed, but began catching up rapidly, except in speech and language. Very quickly, Max grew five pounds and five inches. He soon began walking and running…without the use of his walker! This child with so many question marks was a healthy child who had begun to blossom, right before our eyes.

A month after Max arrived home, however, what we knew in our hearts was confirmed – Max had profound bilateral hearing loss. His paperwork in China stating that his “hearing was normal” was not accurate. Max had never heard a single sound. This also meant that he never heard any of our reassuring words, or songs, or stories in China. He had bonded with us and laughed and played and hugged us, but never once heard us.

In the coming months, we began to develop our plans for Max. We knew we wanted him to belong to both the Deaf culture and the hearing culture. American Sign Language was non-negotiable to us. He needed a way to communicate, and he needed a language that would always be accessible to him. Max did end up receiving bilateral cochlear implants to help him begin to access sound and the hearing culture, but before we agreed to cochlear implants, my husband and I made the decision that Max would grow up bilingual and bicultural – he would learn both American Sign Language (which meant that WE would quickly have to learn ASL!) and English.

He would also be given the tools necessary to function in the Deaf world and in the hearing world. In short, we wanted him to have the tools needed to belong wherever he identified with, and we wanted him to have the choice to communicate in spoken and written English, in ASL, or in both. It is not the most frequently chosen option for children with cochlear implants, but we wanted Max to have the benefits of two languages. He lived the first two years of his life with no form of communication – we wanted to ensure that he was never again left without a way to communicate.

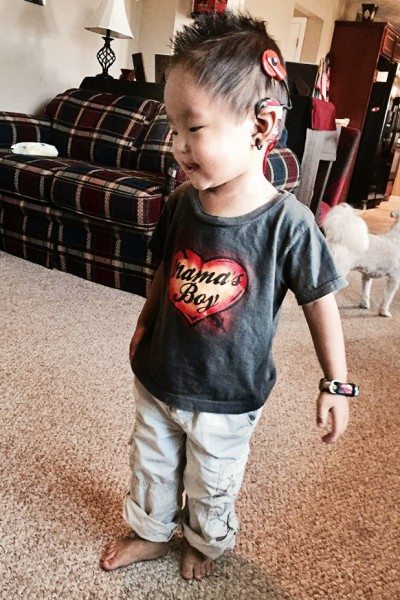

Today, Max is a very healthy and happy toddler who knows close to 200 signs and has begun putting them together in sentences. He is also “learning to listen” with the help of his cochlear implants. He is the sweetest child and makes friends wherever he goes. And we learned that we could bond with a child even if we didn’t share verbal communication. With the help of American Sign Language, we do everything with Max that parents of hearing children do – we read books, sing songs, tell jokes (Max has a fierce sarcastic side! Did you know toddlers can snark in ASL?).

We learn and play and have conversations. We have bonded and we have fallen in love with each other. After all, love is a universal language.

Resources

Learning American Sign Language:

Signing Time DVDs

Lifeprint

Signing Online

Cochlear Implants and Education:

Clerc Center

ASL/English Bilingualism:

Bi-Bi Education

Reading Rockets

Bilingual Consortium

Bilingualism Fact Sheet

Deaf Culture:

Facebook Group for Parents of Deaf Kids: Sign Language, Community, Culture

Our Family’s Non-profit:

Mary di Rosa Academy (Providing ASL lessons to families with deaf children, free of charge, as well as offering bilingual ASL/English educational opportunities for all interested children.)

~ guest post by Allison

Leave a Reply