Today we finish out our month-long series on disruption with a post by Amy Eldridge of Love Without Boundaries Foundation. We are so grateful to include her voice of experience here, as she has spent years working on behalf of orphans in China and has witnessed the wake of disruption on families and children – her insight on this subject is invaluable.

If you haven’t read the previous posts in this series, we hope you will. Disruption is a heartbreaking reality, but with education, support and preparation, it is our hope that even one disruption might be averted. We featured an introductory post with disruption facts, and followed with posts from three mothers: a mother who adopted a child from a disruption, a mother who disrupted during the harmonious period while in China and a mother who, despite significant, undisclosed issues discovered while in China, chose to complete the adoption. Thank you to each of these moms for sharing their very personal story.

I’ve had the honor of working with orphaned children for the last 12 years and have said many times that nothing can change their lives in a more profound way than adoption. Having a permanent family not only allows a child to belong and be loved, but it also gives many children, especially those with special needs, access to education and continued medical care.

When a child in one of our programs is chosen by a family, whether domestically or internationally, I am always so happy to know they’re getting a chance to be someone’s treasured son or daughter.

I wish I could say that is always the outcome, but there have been many times over the last decade that children have been returned to the orphanage when the adoption process was disrupted. And then a shocked adoption community almost always reacts by asking how anyone could change their minds and send a child back to institutional care. It seemed so black and white to me as well in the past. If you made a commitment to adopt, then you had a moral duty to bring that child home, no matter what.

But once orphan care and adoption became my daily life, I began to see that it’s much more complicated than that. Rushing to judge the family or the child during a time of high emotions is rarely productive. Now when a child in our programs is disrupted, I feel only sorrow for everyone involved, but I then remind myself that perhaps it means the particular family isn’t the right one for that child. I learned that lesson in the most awful way possible.

Many years ago, I was called by a family adopting a little girl I had met many times in China. She was very serious when you first met her, but once she warmed up she had a great smile and a gentle personality. The orphanage nannies liked her very much, and she had many friends in her preschool room.

I had no reason to think her adoption would go any way but positive, but then the adoptive father called me from China and told me quite bluntly that they didn’t like this child. That she was sullen and withdrawn. I encouraged them the best way I could and told them to give it more time as her whole world had been turned upside down. A few days later the mom called me – to complain that the little girl smelled terrible and seemed more like a boy in the way she carried herself than the dainty girl they were expecting. I was truly taken aback by the tone of the call, but assured them she was a kind little girl and to give it more time.

The last call I received was the day before they left China. The father told me tersely that they still didn’t like her, but they were going to bring her home because legally “they had to.” I hung up from that call heartbroken – and extremely worried. I never heard from the parents again.

A few years later, I received a phone call from a social worker who was trying to piece together this little girl’s story. The parents had never bonded with her, and in fact had emotionally and verbally abused her for years, addressing her as “Monster” and not letting her eat with the rest of the family. She had finally been removed from their home and was placed into state care.

I cried so hard that day after hanging up the phone, knowing I had played a part in convincing the family to bring her home. I will carry that regret with me the rest of my life. How I wish they had disrupted in China, as the gentle little girl I knew could have gone back to her known life in the orphanage and waited for the right family to choose her, a family who would love her for exactly who she was. Instead she had come home with parents who had decided they didn’t like her while still in her birth country, and she paid the terrible price of being told for years that she wasn’t good enough to be their daughter.

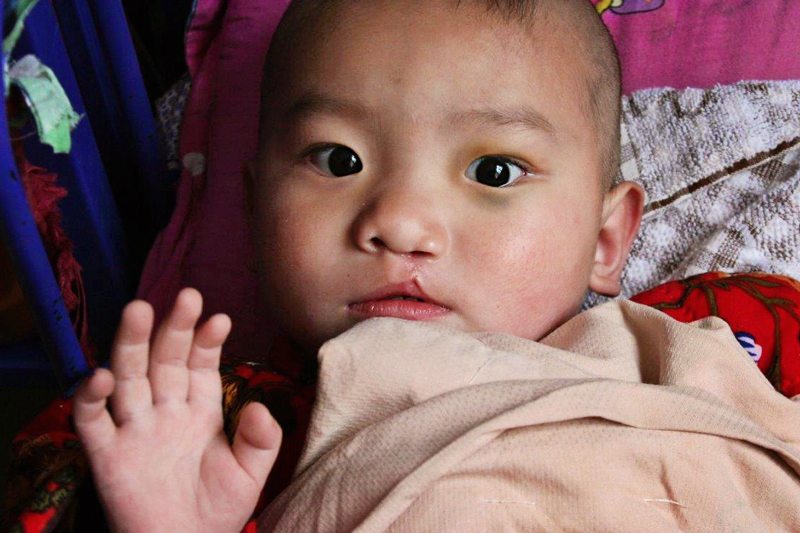

I have heard countless reasons from families and orphanage directors on why adoptions have ended in disruption. Some are a bit bewildering, like the family who disrupted a baby with cleft because milk kept coming out of her nose or the family who disrupted a child because she struggled with walking, even though her adoption file clearly stated that she had lower limb issues.

The majority of disruptions are due to behavior, of course (too wild, too withdrawn, too clingy, too angry). These can be agonizing times for parents trying to decide if a child’s behavioral responses are due to the stress of being handed over to complete strangers, or if they are seeing behavior they fear could throw their lives into complete turmoil. Some disruptions I have seen stem from a parent’s own personal belief on things, such as masturbation, a known self-stimulation behavior for older kids not touched or hugged growing up, but a behavior that different people view in very different ways. Then there are really complex and difficult disruptions, involving non-disclosed conditions such as autism, mental illness, or sexual abuse, which are definitely topics that are rarely black and white.

Few people go into adoption thinking it could end in disruption, just as few people plan a wedding while contemplating their divorce. I don’t believe anyone makes the decision to adopt from a foreign country thinking they will fly across the ocean and then change their minds, but the reality is that it happens every single month.

In working so many times with disruption, there are three key things I wish more people would consider:

1. It is essential to talk through every possible scenario you can think of with your family, so you aren’t surprised when you get to China.

Research the worst complications for your child’s special need, even if they aren’t noted in their adoption file. If you’re adopting a child with spina bifida, for example, learn about tethered cords. If you’re adopting a child whose file clearly states “developmental delays,” don’t just research physical delays but intellectual ones as well. Have open discussions about the behavioral possibilities you might face. What happens if your child lashes out with anger at being taken from all he knows and even physically fights you to get away? What happens if your child starts self-stimulating at night in your hotel room? What happens if your child seems off the charts wild, or is physically over-affectionate, or completely shuts down?

And definitely ask yourself what you will do if you get to China and don’t immediately feel a connection to your new child. I’ve talked to many parents who say disruption could never happen for them because they want the adoption more than anything in the world or because God placed it on their hearts, but I’ve seen plenty of people who were 100% committed to a child before travel still end up stopping the adoption in-country.

2. Don’t ever leave for China without a list of at least three trusted people you can call and be totally honest with after receiving your child.

With one recent disruption, the family felt completely isolated while in China and couldn’t reach their agency. They had so many questions and concerns about what they should do, but they weren’t able to connect with someone they trusted. The only person they could talk with was a Chinese guide who was hired through the travel service, and he had no idea about orphanage behaviors or whether what they were experiencing was in the realm of normal.

There is of course a lot of shame surrounding disruption, and I think some people are afraid to openly admit things aren’t going well. Don’t leave for China without at least a few “lifelines,” even if you think you will never be faced with such a decision.

3. PLEASE DON’T BLAME THE CHILD ONLINE IF YOU DISRUPT.

Yes, that one needs all capital letters. I know in the age of social media that it’s a terribly embarrassing thing to disrupt, especially if you have a whole host of people following your journey online. I understand that families feel a need to justify their decision, especially since there is a tendency to vilify people who end a child’s adoption.

However, if everyone was honest with themselves, the very WORST time to try and explain a disruption is when you are in the middle of such emotional chaos. Parents are often exhausted and jetlagged; they have just made a decision that will impact their lives in a major way, and they are dealing with the pain and grief of having their adoption dreams shattered. That is never the time to blame the child, and the key word in that sentence for everyone to remember is that we are talking about a CHILD.

I wish so much that parents in the middle of disruption wouldn’t diagnose children online with labels like RAD, mental retardation, or sexual predator. While any of those labels could end up being true, few of us are probably equipped to make those definitive diagnoses on our own after spending just a few hours or even days with a child. I have seen those labels stick for years post-disruption, and in many cases they simply weren’t true.

I honestly wish it was an agency rule that parents who disrupt are prohibited from posting anything about the child online. Especially not until the agency, the orphanage staff, and medical experts can review everything that happened once emotions are calmer.

Thankfully, the vast majority of children I know who were disrupted in-country have gone on to be chosen by the exact right families for them the second time around. But therein lies one of the biggest questions – how can we ensure that as many children as possible are placed permanently in families the very first time?

I know that is far easier said than done, since every child and every family comes to the adoption with their own unique histories. Without a doubt, disruption is a topic that brings out very heated opinions, but it is a reality that we in the adoption community shouldn’t ignore. If more families and agencies are open and honest in discussing the “what if” possibilities, perhaps the number of children being returned to orphanage care will grow smaller every year.

In her work at Love Without Boundaries Foundation, Amy has written a blog series to help parents as they prepare to meet their new child.

Please consider reading through this excellent series, it will be such a wise investment of your time on behalf of your growing family and, most of all, your new child.

You can read all of Amy’s Realistic Expectations posts here:

Realistic Expectations: Cleanliness

Realistic Expectations: Potty Training

Realistic Expectations: Clothing

Realistic Expectations: Child Preparation

Realistic Expectations: Food Issues

Realistic Expectations: Attachment

Realistic Expectations: Parasites

Realistic Expectations: Post-Adoption Struggles

We knew a family who had the terrible experience of a disrupted adoption after two years. Her three older adopted daughters had to stay in their rooms with their doors closed much of the time to keep from being assaulted by the newest addition. Mom had homeschooled all the children, but for respite, needed to place this youngest in the school system (at the advice of the child’s counselor). At first, the teacher thought she could handle him in the classroom but he was soon transferred to the Comprehensive Development Curriculum classroom because he was acting out severely in the first grade room. Even their specialized classroom and additional training could not deal with his issues and he was referred home. He was seen daily at home by counselors and was suggested to be sent to an institution. Before committing him to that, they chose respite care with a psychologist where he would be the only child in the home. This WORKED for him and the respite home agreed to take him permanently. I thought with the unfortunate stories listed here, it might be heartening to hear one where the family was experienced and quite loving and went to great lengths to remain the child’s family but it just was not possible.

Hello,

The child in the first photograph of this story (the little one with the repaired cleft lip) looks exactly like our newest son. He came home to us this past November. Is there any way to get more information about that child? It would be amazing it that is our son.

Thank you so much.

Christine Stranahan

We arrived in China just days before 9/11. Once 9/11 happened and we were stuck our son’s behavior was getting worse. Our agency wouldn’t respond and we had no one to call or even talk to. We were so afraid to disrupt and yes felt it was now our duty. We brought our son home anyway. Our agency was no help at all. After years of a very difficult life for us and our son (he was never abused) we finally got a diagnosis of autism, Neuro problems from high lead levels, and attachment disorder along with his cleft palate which we already knew about. The years following were hell on us however after many hours of therapy for us and our son he now is a wonderful 15yr old boy who is so loving, kind and yes still very much developmentally delayed but he is ours and all our love and hard work has paid off. We at first felt no different than any parent who would have given birth to a child with a severe disability, grieving, and confused. I so wished our agency had prepared us for the “what if’s” and at the very least helped us get through those rough days, weeks and months. Since that time we have adopted 2 other children with special needs, the youngest very severe but because of our difficult journey with our son we were prepared. If we could do it all over again our only wish would be to be better prepared by our agency and have more support from them. Yes we thought about disruption and would never blame anyone for that choice because we know first hand. I would also like to stress none of this was our son’s fault, nor is it any child’s fault and should never be taken out on the child. Be prepared and realistic about what you can and can not handle as a parent. Our son is mentally challenged and you can’t see what is wrong making it more difficult to help him and parent him. There is light at the end of the tunnel as long as you, the parent are prepared and willing to sacrifice. We are past the worst even though it took 14 years!

Thank you for sharing a bit of what no doubt has been an incredibly tough journey for your child, you, and your family. Wow, I am truly moved by what you expressed here. I am so appreciative of all the parents who contribute to “No Hands But Ours.” I am learning so much. If I am blessed enough to adopt from China someday, I am fortunate enough to have all the knowledge that has been shared. I do know that reading about it and experiencing it are very very different. Thank you again, and I pray that you and your family are doing well. I also pray for each orphan to have a forever loving family.