Our adoption journey started with two infant adoptions from South Korea, in 2008 and 2010. Our first was a healthy baby boy; our second, a daughter with limb differences. When we considered adding to our family again, we decided to adopt an older child and looked into the China special needs program. We pondered the medical needs checklist helplessly. We had good insurance, but what kinds of needs could we manage on a daily basis with a busy family of six? Could we provide years of possible surgeries and therapies? What kinds of special needs were more “convenient” than others?

At some point along this journey it occurred to us that no matter how inconvenient a special need might be for us, it was infinitely more difficult for a child without a family. We changed our outlook and began doing the research. In particular we felt pulled toward a child with physical special needs. Spina bifida topped our list as we searched photo listings for the child who would be our new daughter.

In June 2011, I found her. She was a 7 year old girl with repaired lipomyelomeningocele, tethered cord, and bowel/bladder incontinence. She lived in an orphanage, and had been there since being abandoned at a year old. A note left with her detailed the anguish her birth parents had felt at watching her untreated spina bifida derail her growth and development, necessitating decisions no parent should ever have to make. Photos of her showed large, sad brown eyes and a shy, fearful disposition. Orphanage notes said she preferred to play alone, and did not allow people to get close to her. Due to her incontinence she was not allowed to attend school, but instead stayed in the orphanage preschool.

As we filled out paperwork to adopt her, I started to prepare myself for the types of care I would need to provide for her when she got home. I learned a lot about how incontinence caused by spina bifida and anorectal malformations affects children socially and physically, when the causative conditions are untreated. For example, many children are classified by China as being regular and not having constipation, because they have a bowel movement each day. However, the vast majority of children with these untreated conditions suffer nerve damage affecting the ability of the intestines and colon to push stool through and to release it on a regular basis. Once the colon is full, stool will fall out, but the colon is stretched and any sensation is lost, making toilet training difficult or impossible. Children can benefit from bowel management programs which use laxatives, enemas, and dietary changes to produce a bowel movement each day and achieve social continence.

However, with overcrowded orphanages, poverty, and short-staffing, children in care in China are unlikely to have these opportunities. Instead, they face a lifetime of shame and separation, where foster families are unwilling to bring them home, schools reject them for the inconvenience and odor, and opportunity for education and social integration is nearly impossible.

As I prepared to travel in June 2012 to adopt our daughter, I considered the challenges that might be involved in managing the incontinence of an older child. Our daughter would have been used to a lifetime in a diaper, without a regular caregiver. Would she trust me? Would she be willing to let me try to help her?

Our adoption day was full of surprises. Our daughter walked confidently into the civil affairs office and sat in my lap. She was shy but sweet as she carefully touched my cheeks and searched my face for clues as to what kind of person I was. She eagerly gave her fingerprint to be adopted and in the weeks that followed, began to blossom!

As she settled in we started the medical workup to assess the range of her needs. It was determined that she could benefit from clear intermittent catheterization and bowel management. One thing that many parents find surprising is how little doctors know about the day-to-day management of these conditions. It’s one thing to learn about incontinence, but another to live it. Most of us find that doctors provide a good starting point for advice on how to manage, but because every child is different, and we ultimately find trial-and-error to work better for managing our kids’ needs.

For example, children with spina bifida experience many different symptoms related to incontinence. Some children are completely continent, or are continent but need to use the restroom on a regular basis, rather than using sensation to decide when to go. Some children may have the sensation of having to urinate, but cannot control it. Some have a neurogenic bladder, in which signals between the brain and the bladder are interrupted by spinal cord malformation, leading to a bladder that spasms constantly but cannot release or hold urine effectively. If the child is not catheterized regularly, damage results from the bladder’s pressure becoming too high and the urine can reflux into the kidneys, causing problems with kidney function. Finally, urinary tract infections are an issue where the bladder does not empty correctly, causing health concerns. Many of these children benefit from a medication such as Ditropan, which stops the bladder spasms, and catheterization, which completely empties the bladder.

Over the course of several months, I slowly introduced catheters and laxatives. Our daughter was nervous at first but agreed to try the protocol that was recommended. It wasn’t long until she was dry and wearing underwear, and we were using glycerin bulb laxatives and cone enemas to empty the colon each day. We use the “bucket approach,” which says that the colon is like a bucket. When a bucket is full, it spills over, but if you empty the bucket each day, you have another day to slowly fill it and empty it before it can spill over. This has worked successfully for several years.

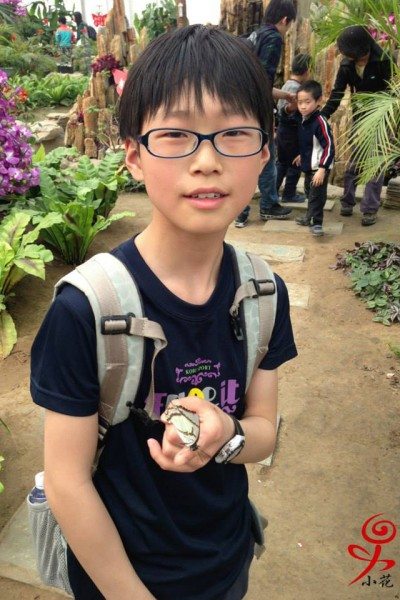

In 2013, I happened to come across the story of a young man who was aging out of China’s adoption program. An outgoing, smart, sweet 13-year-old boy, he had imperforate anus as one of a constellation of symptoms related to VACTERL association. His incontinence had led to his abandonment, and it had caused him to be kept out of school and foster care while he spent his life in an institution.

While reviewing his file I was touched by his hopeful smile, and his statements that he would like to be adopted. I cried reading about how, as a result of bowel incontinence, the students’ parents at his school had called for his expulsion. My husband and I considered what his life would look like if he stayed in China, without access to lifesaving medical care and the tools to achieve daily bowel continence. And then, we said YES.

I traveled to China and adopted him in March 2014, while my husband stayed with our other children. Those days in China were not easy, though my son and I can laugh about it now. He, too, walked willingly away with me toward his new life, and apart from being nervous and active, adjusted easily into his new life. We found that he was lactose intolerant, which negatively impacted efforts to achieve bowel management. However, with the use of a Miralax cleanout followed by daily high-volume enemas, he too found himself continent. Within just a month or two he had learned to measure the ingredients for his enema and to administer it himself. Today, both children manage their own incontinence and are proud of their ability to blend seamlessly into their peer groups, after a lifetime of segregation and humiliation.

There are some things I’d like to mention that I think are unique to achieving social continence in older children. For example, while we may be anxious to begin the journey toward “fixing” the child, it’s important to take the child’s lead. You may think that incontinence is the end of the world, but it is your new child’s “normal.” I was not prepared with either adoption for how comfortable my children were in diapers. I had imagined that both would be excited and eager to wear underwear and to manage their conditions. Instead, both found it easier to be in diapers, without having to stop to go to the bathroom or to learn new ways to stay clean. However, I always prioritized bonding and building trust over imposing invasive procedures. I made sure that both kids were ready and really understood what we were undertaking. They were willing to try the techniques I introduced, but weren’t overly excited about the goal. There are no words to describe either child on the first day of successful continence. My son was amazed that he, too, could wear underwear like everyone else. It was clear that he had lost hope of this ever happening… and he was thrilled by this development!

On the other hand, I also think that undergoing such sensitive and invasive bowel and bladder management built trust more quickly. I promised them that I would help them to stay clean and feel healthy, which no one in their lives had done before, and I followed through with my promise! We learned together and grew together. We laughed together over messy failures, and celebrated successes together. Catheterization forced us to focus solely on each other at regular points in the day, around everything else that was going on. They opened themselves up to vulnerability and saw that my husband and I didn’t reject them for their incontinence, or disapprove of their conditions, as so many people had.

As time went on and our relationship grew, they both shared some very humiliating stories of abuse and neglect which was cathartic for them. We have always made a point to honor those memories and to treat them gently, and to nurture the present, so they can overcome some of the trauma which resulted from their incontinence.

Related to this, I think it’s worthwhile for parents to really consider the social and emotional effects of incontinence as it relates to our children. There is no simple fix here, folks. For adoptive parents, it’s a medical condition to be managed. Honestly, it always surprised me how often people overlooked incontinent children for others whose needs I’d consider more involved, since it seemed a nonissue for us. But for the older child, it is the central focus of his or her life and the source of most of his or her negative experiences in life.

Children are acutely aware that they were abandoned because of their medical conditions. They have watched other children be adopted while they waited due to their special need. Many, if not most, children have been denied an appropriate education, field trips and excursions, foster care, and warm relationships and have been told in no uncertain terms that they smell, or that they failed to potty-train normally. They have been mocked about their conditions and it is the source of great shame.

In your home these memories will compound the typical challenges associated with older child adoption, which are to be expected as a child settles into life with a new family, siblings, language, food, educational system, expectations, and culture. You will need to gingerly approach social continence without putting your child on the defensive or making the child think you believe he or she needs to be “fixed” to be good enough. You will ask questions about bathroom behavior and your child will try to size up whether you are mocking them. Any accidents will be hidden in anticipation of discipline or scorn.

Eventually, you will realize at some point that the hurt is so very deep, and the child’s self-esteem has been damaged so severely, as you slowly pull apart the layers of your child’s personality. You will realize that incontinence has affected the child so much more than physically, and that so many seemingly unrelated experiences your child has had really stem from the medical condition that put your child in the situation.

You will slowly conclude that long after your child achieves social incontinence, he or she will still remain an “incontinent” or “disabled” child inside, with the stigma and shame, and that it will be up to your lead and your child’s resilience to change this. It will be up to you to patiently rebuild the child’s self-esteem, while showing him that his identity is so much more than what happens in the restroom.

And one day, after many other exhausting and difficult days, you will realize that it’s been a while since you comforted a crying child after an accident, or found a hidden pair of stinky underwear, or treated a urinary tract infection, or had a conversation about poop at dinner, and you will realize how far you have all traveled, together. Your child will realize that her worth is bigger than her trips to the bathroom. Incontinence will be just another feature of your child’s life, like his eye color or his favorite color, rather than sorrow that is written upon his soul.

Your future, together, is now.

– guest post by Tracy

Leave a Reply