Rini, our youngest of six children, was adopted in August of 2013 at end stage heart failure stemming from complex, single ventricle congenital heart disease. She was admitted to the hospital immediately upon arrival home and within two weeks it was determined that she was inoperable, her only hope would come through cardiac transplant. She was initially found to be ineligible, but that would change thanks to a heart failure/transplant program that chose to take a chance on hope and optimism.

Much as we owe her life to the sacrifice made by her birth family in letting her go, we also owe it to the incredible, selfless act of organ donation made by a family in the midst of the incomprehensible loss of their child.

This series is a retrospective of the weeks leading up to Rini’s transplant which took place on November 13, 2013, and it is my hope that it will help to bring awareness to the importance of registering to be an organ and tissue donor.

We all have the power to be someone else’s miracle.

Donate Life!

From November 1st, 2016

I have no memories of this day, three years ago. In fact, I have no memories of November 1-4, 2013 other than of taking the photo that I will post on the 4th. My recollections of those days were erased, I believe, by the trauma that occurred on the 5th. So tonight, I will write about Rini’s favorite doctor.

I don’t remember the first time I met Dr. Law, the Medical Director of Seattle Children’s Heart Failure and Transplant Services. I liked that he and Rini were born in neighboring provinces in China, but I wasn’t sure if I liked him. He was a man of few words, didn’t smile easily, and seemed to be prone to negativity. But soon I understood that what I first viewed as pessimism was actually realism. With that, we came to depend on him to be the one who would not mince words and we trusted him to give it to us straight. Eric and I viewed him as the barometer of Rini’s status. If he was worried, we were worried. I now know him as one of the most hard working and devoted physicians I have ever met, and he is who Rini refers to as, “My Dr. Law.”

I remember the night when I caught a glimpse of the soft heart underneath the no-nonsense exterior. I was returning to Rini’s room and saw that he was examining her. It was a couple of months after transplant and Rini was still critically ill in the CICU, but no longer as heavily sedated. His back was to me as I approached her room, and as I came closer I could hear him talking to her. Actually, cooing at her is a more apt description.

“Oh! You’re so cute! Are you trying to wave to me?! Hi there, sweet girl!”

It was an absolutely precious moment between a devoted physician and one of his littlest charges. Not wanting to embarrass him, I quietly backed away and hid around the corner until he had left her room. A few weeks later, Rini was sitting up and playing with Play Doh when her Dr. Law came by and she handed him some. He was befuddled, looked at me with a confused expression and said, “What do I do with it?” So right then and there, my baby and I enjoyed teaching a physician at the top of his field a little something. Rini and I taught him how to play.

From November 3rd, 2016

From November 4th, 2016

On this day three years ago, I walked around our house and looked at all of the reminders of Rini that were there: her portable crib downstairs with the hot pink polka dot sheets, her forest-themed swing, the colorful and tiny baby utensils, her feeding pump, the sweet clothes I had picked out for her that she had not had a chance to wear, her crib next to our bed with the slats that she and I would hold hands through, and the treasured cards and gifts that friends and strangers alike had been sending.

I looked out our second story hallway window at our mature October Glory maples that were stunningly wearing their autumn colors, and I cried. I went downstairs and out the front door and walked underneath one of them and took this photo. I wanted to remember the very moment when my daughter was so fully on my heart, when every ounce of emotion in my soul was focused on her.

She had been listed for transplant for 12 days.

Her heart would stop in less than 24 hours.

November 5th

On this day three years ago, our baby girl’s heart stopped. The hardest week of our lives began. It was the week where we would be bombarded by wildly varying emotions that would come like waves that barely receded before the next one came crashing. I cannot speak for Eric, but I personally encountered the deepest pain of my life thus far, and was taken to places within myself that I never could have imagined existed.

My friends, don’t ever tell someone in the midst of pain that God doesn’t give a person more than they can handle. I certainly could not handle on my own what I was in the midst of. That is where faith came in.

My first memory of the day is of taking our sweet Scarlett to her occupational therapy appointment at Easter Seals. She sat in a swing and expressed such great joy! “Wee!” she said, over and over. It was absolutely precious, and I sent a video of it to Eric so that he could experience the moment for himself. It gave such a sense of gentleness and peace to what would be a day comprised of savage shifts.

I was in our bedroom putting laundry away and it was around 1:30 pm when the phone rang. I put the receiver to my ear and heard the most awful, primal sobbing. It was my husband, who I had never heard cry before. The only words I could make out were, “She’s back.” Stunned and shaking, I told him I was going to hang up and begin packing and called our friends who were on stand-by for childcare. I barely remember throwing my things in my suitcase and making the calls to my friends, although I do remember the love and their take-charge attitudes.

Eric called me back within fifteen minutes or so, and told me that Rini had gone into cardiac arrest.

From my journal:

“Around noon today, Eric called with his after-rounds report and we were both thrilled that Rini had been stable throughout the night, and her team was feeling optimistic. He and I then began discussing our plans to switch places on Friday, including a discussion regarding the mundane things to be done like the laundering of Rini’s blankets. I reminded Eric not to leave her quilt unattended since I was paranoid about a repeat of what happened at the hospital in Portland.

After our conversation ended, he went upstairs to the family resource center to do a load of laundry and he stuck around as the clothes were drying to make sure Rini’s quilt remained in our possession. He received a call on his cell, and it was the nurse from the room next to Rini’s telling Eric to come back to Rini’s room right away. He ran, and when he arrived five minutes or so later he saw medical personnel spilling in and out of her room. When he was able to see in, they were doing chest compressions on her.

They were minutes away from beginning the process of placing her on ECMO when the Epinephrine did its job and her heart rate came back. At that point, he called me and I couldn’t understand a word he was saying through his sobs, but later I could understand his words as he choked out, “She’s back.” It was a quick conversation, and I hurriedly began throwing things in my suitcase and calling my dear friends to put in motion the emergency childcare plans that they had helped to set up.

A bit later, Eric and two of her cardiologists called me, and they told us that they felt it would be a good idea to go ahead and place her on ECMO preemptively. However, over the next hour the decision was made to hold off. Rini has only been on the transplant list for 13 days, and the average wait time in this UNOS region for a child at Status 1A on the transplant list is 3-5 months.

Because she can only survive on ECMO for a few weeks at most (2-3 weeks is about average), we are all very concerned about using up her ECMO time, so to speak. We are basically gambling that we can get her through another hour, day, week, or month before placing her on ECMO. They said the likelihood that she will have another episode is high, and if it occurs again, there will be no question. She will be placed on life support at that point. The crash cart and ECMO machine will permanently reside at the entrance to her room from here on out.”

My dear friend arrived and I headed to the elementary school to pick up MeiLi, who was seven years old at the time. I did not want to leave for Seattle without having a chance to explain to her, an anxious child, what was happening and why I would be departing for Seattle three days earlier than planned. When I reached the school, a friend came over to me to give me a hug as I cried. Another mom I would characterize as an acquaintance walked over to us. How she had heard about what had transpired, I do not know. But her words, delivered with a confused facial expression and in a quizzical tone were, “Well, you knew this could happen, didn’t you?” That is all she said.

I’ve thought a lot about her question, which was actually a comment in disguise, over the past three years. Many adoptive families of medically fragile children have been blindsided by such a comment. The insinuation is that we who choose children with medical needs or disabilities are somehow not entitled to feel the same despair when our children suffer as those who have the expectation of a “healthy” child.

Choosing to love a child whose future is more statistically uncertain than another child’s does not inoculate us against heartache.

It doesn’t make us superhuman, and it doesn’t make us saints. It just makes us people who chose our kids no matter what diagnosis was attached to them. We love our children and grieve for them as deeply as a parent who is in the midst of a surprise diagnosis. Now to be fair, Eric and I certainly had the benefit of experience which altered our expectations of the road ahead. And also, when one chooses a child who is already in the midst of illness, we do so from a place of hope. I certainly didn’t pray for Sophie to have congenital heart disease when I was pregnant with her, and I recognize that such a diagnosis would have been shocking and very difficult to process. But does that mean that those of us who knew the road would be hard when we first stepped foot on it should not be shown support and compassion?

What I suspect is that the rest of her sentence might have been along the lines of, “Well, you knew this could happen so what are you so upset about?” Perhaps people feel that if they keep emotional distance from those who are in pain, and take the attitude that the sufferer is responsible for that pain because they chose to love a sick child, they can then believe that they can protect themselves from similar heartache. But nobody is immune to pain, to loss, to death. Nothing guarantees a life free from tragedy. Not even God.

From my journal:

“I picked up MeiLi from school and then arrived home to the sounds of happiness as our little ones played with my friend’s children, and after hugs and kisses and a tough conversation with our eldest, I headed out the door. It was a four-hour drive to Seattle, and I thought, and thought, and thought. I cried and prayed, and cried some more. One thing I can say is that Eric told me tonight that he feels honored to be in this position, to be the dad to this precious child, even with its heartache and anxiety. I couldn’t agree more as her mom.”

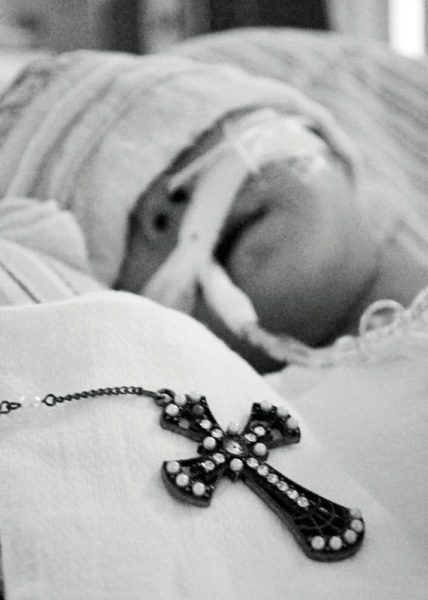

It was pouring down rain during most of the drive, and so very dark. It seemed like every song that came on the radio was speaking directly to me, and several times I had to pull off at a rest stop or service station to collect myself. When I arrived at the hospital, I found my beautiful daughter looking much like I had last seen her, except that her chest was now bruised from the compressions. I laid a beautiful crucifix by her side, given to us by a friend.

Eric and I were taken into the Quiet Room by members of Rini’s team, and it was explained to us that another arrest was not an “if” but rather a “when”. The VAD had not arrived yet. I couldn’t bring myself to ask whether they felt Rini would survive to transplant. I just couldn’t. I knew what their answer would be, and I didn’t want to hear it spoken out loud. Hearing it within myself was excruciating enough.

The Reverend Mark Beckwith writes, “My instinct is to seek — and expect — a spiritual firewall from God. And when I don’t get it, I get indignant, and like millions of others, I shake my fist at the heavens and demand to know why this is happening. I end up looking for a God who will provide protection — and miss out on the God who offers support.”

I struggled mightily on this day, three years ago, and in the tumultuous days and months to follow. I watched as parents… wonderful people, lost their children. I saw believers leave the hospital with their child, and others leave without theirs. I saw atheists leave with, and atheists leave without. People of all faiths and people of no particular faith… nobody was insulated. Tragedy appeared to be the great equalizer.

There’s no vaccine for the pain of this world.

Did that crush me? No. Ultimately, it brought me closer to God and liberated me. Before Rini, when I believed that I could somehow control outcomes, that is when I knew fear. As each day passed and I watched my child suffer complication after complication and the end of her life was so close, I came to a beautiful understanding with God. There are as many beliefs about God’s role in the events of life as there are people, and as many interpretations of scripture relating to this topic. But my belief is that He isn’t the cause of suffering, and He isn’t here to prevent me from experiencing devastation and pain. He is here to carry me through it, and to encourage me to leave the world a better place for having experienced it. And ultimately, for Rini to have a chance at life, it would take another family willing to believe in the possibility that beauty could emerge out of their own tragedy.

Leave a Reply