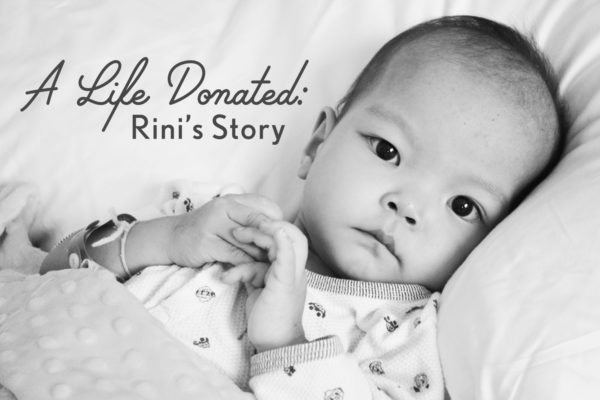

Rini, our youngest of six children, was adopted in August of 2013 at end stage heart failure stemming from complex, single ventricle congenital heart disease. She was admitted to the hospital immediately upon arrival home and within two weeks it was determined that she was inoperable, her only hope would come through cardiac transplant. She was initially found to be ineligible, but that would change thanks to a heart failure/transplant program that chose to take a chance on hope and optimism.

Much as we owe her life to the sacrifice made by her birth family in letting her go, we also owe it to the incredible, selfless act of organ donation made by a family in the midst of the incomprehensible loss of their child.

This series is a retrospective of the weeks leading up to Rini’s transplant which took place on November 13, 2013, and it is my hope that it will help to bring awareness to the importance of registering to be an organ and tissue donor.

We all have the power to be someone else’s miracle.

Donate Life!

From November 6th, 2016

On this day three years ago, we waited in a land of shadows. We were waiting for her precious, tired heart to let us know once again that it was fighting a losing battle. All of us were hoping that it could last another hour, another day, another week. Anything to close the gap between the time she had been on the list and the time when we might expect, based on averages, that a heart might become available to her.

Rini’s doctors let us know that she had been listed to be able to accept a heart from a child as small as 6 pounds up to 35 pounds. Oh God, it was such a terrible thing to be waiting for.

Transplant is an awful, horrific thing to be waiting for. To need another child’s heart to keep my child alive was devastating to me. I’m acutely sensitive, and as a child I endured many stings from when I would reach my hand into my parents’ swimming pool in order to rescue a drowning bee. The memory of hearing the sounds of a rat caught in a trap the exterminators had placed in our attic when I was a little girl still bothers me. The suffering of others is something I cannot help but be affected by, and to be dependent upon the death of another family’s child to be able to offer mine life was something I know I will never be able to reconcile myself with.

From my journal:

“Eric is on his way to SeaTac for his flight home, and I am sitting here behind Rini’s bed with a heavy heart and a lot of anxiety. At rounds this morning, Rini’s team treated us with great compassion as they explained that Rini’s situation is very tenuous and that we need to approach it minute by minute. It is not a question if she will arrest again, but rather when. Whether to preemptively place her on ECMO or reactively do so is a question without a clear answer.

Later today, they will be taking a look at our baby girl’s neurological function since her pupil dilation has been going from sluggish to rapid and they are concerned about possible brain edema. They will also be investigating whether she may be having seizure activity. They defined it as a ruling out procedure, as they are attempting to get to the bottom of spikes they are witnessing in some of her numbers. I apologize for not being able to give more specific information. I’m realizing that I actually do have a saturation point. The woman who usually has an insatiable appetite for information really can’t seem to absorb anything more.

I have spent so much of my life trying to keep things neat, tidy, and tied up into little bundles. Flexibility and dealing with ambiguity have never been easy for me. “You have no patience!” is something I have often heard. Yet here I am, straddling a fence with our child, with death on one side and life on the other. She teeters to one side and then wobbles over onto the other, with Eric and I helpless to steer her in the direction that we hope she will go. I am scared that we will never hear her voice again, or feel her little hand gripping our fingers.”

From November 7th, 2016:

On this day three years ago, it had been 43 hours since Rini’s arrest. I woke up at 8 am after a fitful four hours of sleep. It was a Thursday morning, cold and gray, as many are in the Pacific Northwest in autumn. I had been woken up by the announcement being made that the Cardiac ICU huddle was about to begin, which is when the entire team gathers to discuss the morning’s agenda before beginning rounds. Rini’s room was very quiet, except for the sounds of her monitors and her nurse’s movements, and I walked to the side of Rini’s bed so that I could touch her and whisper my good morning wishes to her. Wanting to shower and be back to her room in time for rounds, I opened the sliding glass door to her bathroom and began gathering my toiletries for my trek down the hall, but decided to brush my teeth before I left.

From my journal:

“Just then, one of Rini’s alarms sounded. I didn’t think much of it at first because alarms are beeping all the time and usually they cease as she levels out. However, the pattern that I have noticed over the past two days has been a cessation after three beeps, and this morning the beeping continued. I got up and went to where I could see the monitors and her nurse was there and she paused the alarm. It was her blood pressure, which had dropped but had climbed back up. I turned and went into the bathroom and began brushing my teeth.”

The alarm sounded again and I looked over at her nurse. Her face told me everything I needed to know. She yelled, “Get the crash cart!” The entire CICU team was gathered just steps from Rini’s room for the huddle, and within a few seconds they were in.

Rini’s heart had stopped. This was it. I slipped out of the bathroom and sat down on my bed at the rear of the room. I felt the most intense combination of utter sadness and total peace. Time seemed to stand still as the incredible choreography of lifesaving measures took place. There were at least 15 people already in her room with more arriving. There was calm within chaos, with each person intent on their role. I remember being shocked at how violent the chest compressions looked, as though they themselves could kill a child.

I talked to God, and thanked Him for many things: for having placed Rini on my heart; for allowing me to take over the role of mom for her birth mother who let her go out of love; for this incredible country and the healthcare available here; for my husband who didn’t even flinch when, after months of fierce advocacy had failed to secure her a family, I had looked at him and said, “I want to adopt her.”

If Rini’s little soul had already left her body but was still in the room, I didn’t want her to see me in hysterics being pulled out screaming. So I did my best to gather all the love I had for her and focus on it. I wanted my precious baby girl to feel free to leave if she needed to, and not to feel any burden because of my emotions. Being with Rini during those long minutes was one of the most precious times of my life.

From my journal:

“I teared up as I watched all of these people fighting for her life. They were fighting for the life of a little girl who wasn’t even fed in the PICU in China, whose orphanage would not permit her to be transferred for medical care in Beijing because, in their words, “….she will die anyway. There is nothing that can be done for her so why are you spending so much time on her?”

Please don’t think for a minute that I harbor ill will towards those who cared for her there. I have great compassion for the predicament they are in. It’s an overwhelmed, underfunded system and so many children are the casualties of it. Every day, more children enter. Every day, more children die. It is endless. On an intellectual level, I completely understand.

Look at the care she is receiving here! There is no way that this level of care can be devoted to just one child in China when there are thousands of others who need it, too. So as I sat there and watched them attempt to save our child’s life, I felt such immense gratitude.”

I called Eric as the arrest was taking place, as he deserved to be present with his baby girl, even if only in spirit. He was very calm. The arrest lasted over 5 minutes, and a weak heartbeat was recovered. I looked to my right and the transplant social worker was sitting next to me, as was the physician who had been assigned to our family as part of the hospital’s palliative support program. She and her colleague would visit families like ours each and every day and would act as a liaison between us and the rest of her team. It was such a blessing, and we never felt lost or alone because of it.

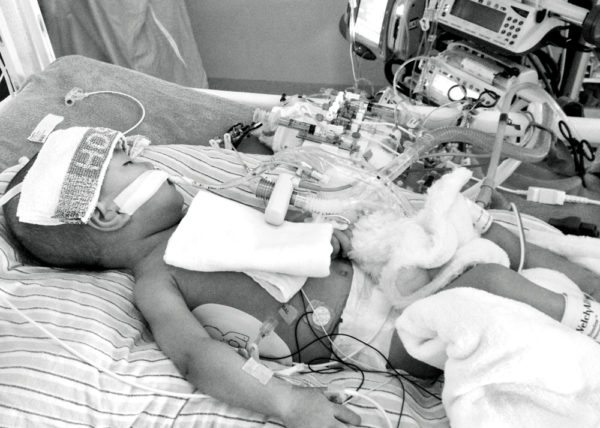

I was required to leave her room at that point, as they were about to place Rini on ECMO. But first, I leaned down to Rini’s ear and whispered words from my heart, and I told her that mommy would be back. I was permitted to return to her room approximately 90 minutes later and was briefed on what to expect. Rini would have one to two nurses in her room at all times plus one to two ECMO perfusionists who would be stationed at her bedside at all times.

Almost from the beginning of her time on ECMO, Rini experienced complications. The ECMO perfusionists sat beside the machine during their entire shift, and every hour they’d perform a detailed inspection of the circuit, checking for signs of clots. By early afternoon, the first clot had been discovered. ECMO is dangerous for several reasons, one being that the high doses of Heparin needed to keep the circuit flowing smoothly can cause internal bleeding, namely in the brain. In some cases, Rini being one of those, the child is a chronic clot former despite appropriate Heparin dosing.

From my journal:

“A few hours after ECMO started, she developed a clot which was caught during the hourly check performed by the two ECMO specialists on shift. Because of the danger of the clot breaking lose and traveling into her body, it had to be removed. It took about an hour to prepare everything, and for the two specialists performing the intervention to rehearse the process multiple times.

They planned it, vocalized it, and then acted it out over and over while being timed until they were confidant they would be able to intervene as quickly and safely as possible. I was permitted to stand right outside the door and watch. The ECMO circuit was turned off, thus ceasing circulation in order to stop the blood flow as they cut the plastic tubing, removed the portion containing the clot, and then reattached the tubing to the machine. The entire process took just 150 seconds. Her heart rate dropped of course but as soon as the ECMO was turned back on, it went right back up.”

Several hours later…

From my journal:

“Her room has been filled with team members all day, and it became apparent pretty quickly that they were having trouble with perfusion. Everyone is born with a little tunnel between the aorta and pulmonary artery known as the Patent Ductus. In most newborns, it closes within a few days of birth. But in some children it remains open, and is then a cardiac defect known as patent ductus arteriosis (PDA). Rini has a PDA, and in her case, it helped her single ventricle anatomy by allowing mixing of oxygenated and unoxygenated blood. Because of her severe pulmonary stenosis, which kept blood from being able to get to her lungs for oxygenation, her PDA permitted some blood to make its way into her lungs through another route.

During her heart catheterization in September, her PDA was stented open to allow more blood flow into her lungs in an effort to increase her blood oxygenation. But now that she is on ECMO, that stented PDA is causing big problems. ECMO is circulating blood through her body but the blood is being siphoned off from her systemic flow and into her lungs through the PDA.

She also has two large collateral vessels that have formed that are also sucking blood down into her lungs. This is making it difficult for her brain, kidneys, liver, intestines, and body tissues to receive the necessary blood flow, plus it’s causing there to be way too much blood flow into her right lung.

Her left lung is not functioning (it is crushed under her enlarged heart), and her right lung has already undergone damage for receiving so much blood flow over her lifetime. With only one viable lung, it is imperative that her right lung be as protected as possible in preparation for transplant.”

75% of Rini’s blood was shunting directly to her right lung rather than making its way out to her body, a situation they termed as “dire”. I was taken to the Quiet Room and Eric joined via conference call. One of the interventionists and a transplant cardiologist discussed with us that they were preparing to take Rini into the cath lab where they would be partially or completely occlude the PDA and the collateral vessels depending on what they found.

The conversation then turned to the VAD (ventricular assist device) that had arrived. Given this turn of events, Rini would no longer be a candidate for it. The VAD would not be compatible with her anatomy once the PDA was occluded, since there would be no way for her blood to be oxygenated (a VAD does not have an oxygenator as ECMO does). It wouldn’t have been compatible anyway, regardless of the PDA occlusion, as illustrated by her hemodynamic shift on ECMO. It was a somber point in the conversation, with the physicians making sure we understood completely that ECMO was now the only bridge there would be for Rini. It felt like the tunnel we were in with Rini was narrowing and growing darker by the minute.

By that point in the day I was completely shaken and numb. It is only by looking back that we can see how incredibly close Rini came to death on so many occasions. I had no time to catch my breath on that day or to really digest all that was happening.

The cath took over six hours, and it was close to midnight when we settled back into her room together. The collaterals and the PDA were completely occluded, resulting in a wonderful ten point rise in her blood pressure. Her rhythm began to go askew so they did a chest x ray to make sure the occluder had not shifted (it had not).

I’ve never been as aware of time as I was once Rini was placed on ECMO. It had become our most precious commodity and our biggest adversary.

Leave a Reply