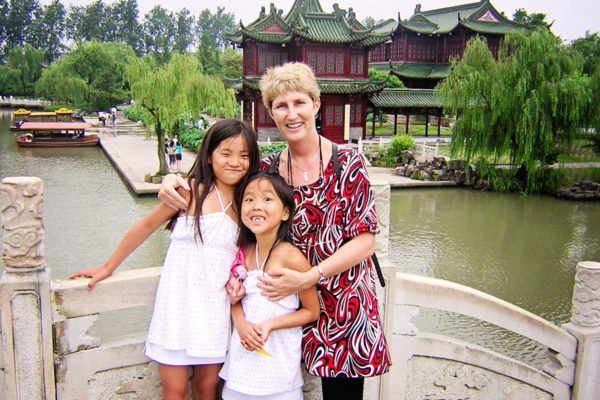

Patti Waldmeir, award winning author and foreign correspondent, raised her adopted Chinese daughters Grace and Lucy for half their life in China. She’s just published a book about raising them in the country that could not keep them…

“Do they know they’re adopted?” Soaking naked in a rosewater hot tub in a Shanghai spa – or letting tiny fish eat the dead skin off my feet at a beach on the East China Sea – or waiting in line for Swedish meatballs at the Shanghai IKEA – for all the eight years we lived in China, everyone wanted to know the same thing. Did my kids know they were adopted?

The question always came in a whisper, in case the children had perhaps not noticed up to then that their hair was straight and black while mine was curly and grey, and our skin tones could not possibly have been produced by the same gene pool. Cross-racial adoption isn’t the kind of thing that anyone can keep secret for long, but most of China seemed willing to believe that I had somehow managed it.

Every taxi driver seemed to think their whole life story should be dispensed along with the fare: abandoned at birth, on a Chinese roadside, in winter, adopted by a single parent in her mid-forties, taken to live in Shanghai at age seven and eight — can we get out of the cab now? And ever cabbie had the same verdict: I was as virtuous as Mother Teresa for adopting them, and they should be grateful for the rest of their lives that I had done so.

It was very good for the ego, being an American adoptive parent in China: everyone seemed to think only a saint would adopt across the ethnic line. Nobody believed me when I insisted that I had adopted my girls for precisely one reason: because I wanted babies. Not for their sake – for my sake. I’m sure some, if not many, adoptive parents have more laudable motives than that, but I can honestly say that I did not. I just wanted me some babies.

I thought long and hard, though, about adopting kids that didn’t look like me. For my part, what they looked like was irrelevant: my original plan was to adopt African babies, after living on the African continent for 15 years from age 25 to 40. But I was worried how everyone else would take it. Would the world accept our multi-racial family? Would we fit in better if the kids were Chinese, rather than black? Or would the kids still pay a price for this act of parental colorblindness? Would they resent being raised to be white, when on the outside, they were nothing of the sort? Would they one day blame me for taking the China out of their souls – before it even got properly rooted there?

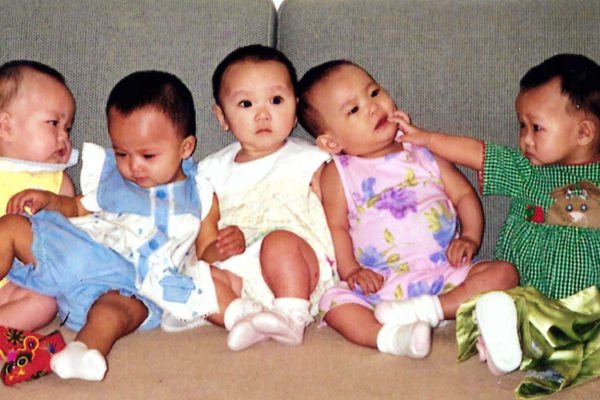

For I have always felt that, at the heart of every Chinese adoption is a tragedy beyond measure: in the moment they were placed in my grateful arms, they gained a mother who would always adore them — but they lost another mother whose breasts still leaked milk for them on the day they were abandoned. They lost brothers and sisters, ancient ancestors, all stripped off the family tree fractured by their abandonment. Name, birth date, nationality, ethnic identity, and family medical history, all gone, along with even the faintest memory of the past, the culture, the history they were born with.

So in 2008, I had what I thought was a bright idea for dealing with that issue: let’s all move to China. Once there, I went at the familial cultural revolution project with a vengeance, determined to introduce Grace and Lucy to “the real China” — by which I apparently meant: China with all its cultural differences from the west on maximum display. On school holidays, when their international school classmates went to Bali or Paris, I dragged Grace and Lucy off to a town in southern China where every restaurant only sold dog meat. By that time, most of the rest of China had given up eating canines but I found the one place where dog was still a delicacy, and paraded Lucy past the wok full of simmering puppy paws at the door, to a table of brown dog hotpot. Grace, thinking of our own brown puppy, Dumpling, refused to come inside. The sins I committed, in the name of acculturation.

We visited their orphanage hometowns on multiple occasions, guests of the Chinese government, which threw lavish “welcome home” parties for overseas adoptees, to expiate the cultural shame of having had to send them overseas in the first place. Grace came back from Yangzhou, her mainland hometown, laden with a pink teddy bear bigger than she was — and with memories of visiting her orphanage in the company of former cribmates who now live in the US. Lucy’s orphanage director waltzed her through the social welfare institute that she called home for the first year of her life, under a vast LED screen that proclaimed her welcome.

Did that just leave Grace and Lucy feeling uncomfortably trapped between America and China? I anxiously interrogated them from time to time, as to how all this was sitting with their psyche. But, maybe because adoption has always been such an obvious fact of life for them, they professed not to give a hoot about it.

They cared that I was old enough to be their grandmother, they cared a bit that they had no father, but adoption, and by a white person? They considered that normal: after all, many of their best friends were cross-racially adopted. The only thing Grace and Lucy didn’t like about adoption was the fact that other people seemed to find it strange.

On their first day at their bilingual Chinese-British school in Shanghai, the teacher asked where each kid was from. “The other kids were saying, ‘Half Chinese and half Finnish’ or whatever, and they got to me, and I said, ‘I dunno, Chinese-American-adopted sort of, I guess?’” said Lucy. “Everyone was like, ‘OK, that’s a bit weird,’ and moved on to the next, who just said ‘French’. It was like there was supposed to be one right answer, but I didn’t know what it was,” Lucy recalled years afterward.

And now we are back in the Midwest, my original home, as the girls finish high school in a place that is, appropriately, anything but lily-white. And everyone is surprised to find they are not what they seem: Grace and Lucy are always presumed Chinese until proven otherwise. In the US, they are constantly complimented for how well they speak English, even though it is their native language; in China, they are expected to speak Mandarin perfectly, though for them it is a foreign tongue. They constantly surprise people, and sometimes disappoint them, because they do not look like what they are.

Now, as they apply for college, they are facing questions such as whether to admit to being Asian on college applications. Both girls have heard that there’s a bias against Asian students, especially in the better universities. With names like Grace and Lucy Waldmeir, they can assume the cultural mantle when it suits them — and shrug it off when it does not. But both of them are quite sure about one thing: they decided to write their college essays about returning to China last summer to volunteer at an orphanage. They know a good cultural sob story when they see one.

So how did our cultural revolution work out in the end? Is it possible to teach someone to be Chinese, by carting them off to China and taking them to dog diners? What does it mean to be born into one race and raised by another? Or, for that matter, what does it mean to be Asian-American in the United States today? Or Anything-American?

My children are maturing in a two-power world where both sides are ever more virulently attached to their own identity as a nation. Will they feel caught in a no man’s land between dueling nationalisms or stand strongly with a foot in each camp and help the rest of us straddle that divide? Grace and Lucy have changed their tune on this stuff so often that I’ve lost track.

And why shouldn’t they? Identity isn’t a fixed thing, ethnic or any other kind. I can only confidently say that I may never really know how they feel about being Chinese. I just hope they will figure it out, eventually. Maybe that’s why they asked for 23andMe DNA testing kits for Christmas last year and why one daughter announced she wants to tattoo her Chinese name on her ankle in perpetuity.

Living in China marked them forever. Coming to terms with Chineseness: that will be the work of a lifetime. But for them, not me. I’m glad I gave my children access to that Chinese part of themselves (and taught them Mandarin), whether they wanted it or not. I’m even more pleased that I discovered there would always be a Chinese part of me, too. Are we all Americans or Chinese or both or neither? I’m not going to stress about that any more. Perhaps that’s the most fitting end to our unlikely love story: that we all get to be accidental Chinese-Americans together, no matter what we look like.

Patti Waldmeir‘s book, Chinese Lessons: An American mother teaches her children how to be Chinese in China, is available on Amazon.

Leave a Reply