One question that plagued me into adulthood was this; “Why was I one of the lucky ones?” After visiting China and seeing many children in poverty or abandoned and in orphanages, thinking about the ones who wouldn’t make it because of sickness or because of a broken system that can’t care for it’s own children, this question haunted me.

Another topic necessary to address the former is The Obligation to Return. Especially in my adolescence, I had an increasing desire to go back to China, to see for myself. I was able to return when I was 16. When our plane landed and I touched on Chinese soil for the first time in my memory, I thought, the woman who gave birth to me is somewhere, here.

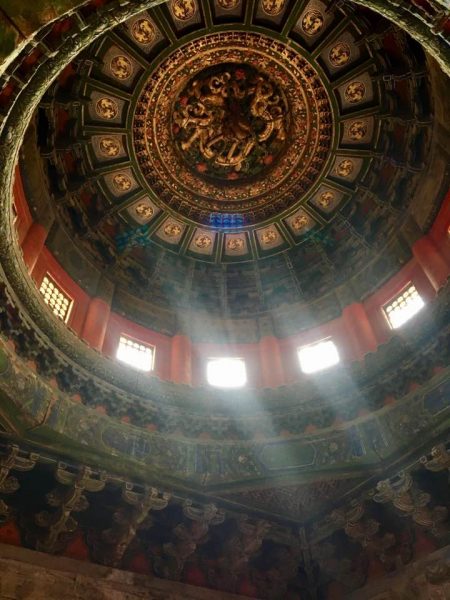

The obligation to return didn’t stop there. With my adoptive parent’s support, I went back a second time. Now I am here for a third and staying for a year in Beijing. Not until recently did I learn that this deep-seated feeling of obligation is somewhat normative for adoptees. Seen more commonly in adoptees placed at older ages, though not uncommon to adoptees placed as infants (like myself), the call to return may come from various places. Maybe it is from a desire to connect or reconnect with adoptive parents, siblings, or loved ones from the child’s early memories.

It is quite common for adoptees to create fantasies about their birth parents and the hope to “rescue them” one day. I admit that I have my own fantasies about one day meeting my biological mom and dad. Maybe the adoptee wants to be among the country or people that he or she was born to. Regardless of cause, this obligation may exist for the adoptee, or it may not. For some adoptees, such things never come to mind. For others, these themes run through their lives.

For an adoptee, the return can stir up feelings of guilt. Conversely, the feelings of guilt may motivate an adoptee to return and begin the search for their biological family. This guilt may be a form of Survivor’s Guilt, which can prompt an adoptee to ask, “Why was I given every good thing in the world? And why did the baby who slept next to me in the orphanage grow-up in the system?”

This guilt, or the sense that one has done something wrong, is often felt by adoptees. Closely related is shame, the ongoing feeling that one is fundamentally bad, inadequate, or unworthy. Guilt and shame are often felt when an adoptee deals with feelings of loss, rejection, or abandonment, which most adopted children face at one point or another.

I can’t quite recall the specific time when I began to consciously notice feelings of guilt and shame. Psychology tells us between the ages of 3 and 5. I think that I may have been 8. However, guilt and shame were manifested in my actions of “people pleasing”. Adoptees so often desire everyone to be happy. In an unjust world, so few are. Somehow, this becomes the fault of the adoptee.

We often explore scenarios of lives that we could have lived; a broken home, the orphanage, poverty, the street even. These become especially prominent when an adoptee visits his or her birth country or reunites with birth parents. If we have good lives, great families, never a worry about food, housing, clothes, education, we ask, “Why?”

These feelings aren’t necessarily a bad thing. On the one hand, they show that the adoptee is developing and expressing empathy for others, gratefulness for what they have, and senses of duty and loyalty. However, when these feelings of shame and guilt begin to weigh on the adoptee so much that they interfere with their daily functioning, this is problematic.

What can an adoptee do to order these emotions rightly but to still continue to grow in empathy?

1. Talking with family, friends, and trusted loved ones is a good way to help the adoptee reduce feelings of isolation and helplessness. Seeking the professional support of a counselor may be needed as well. I sought counseling in college and gained the comforting piece of knowledge that the thoughts and feelings I was having were normative for adoptees.

2. Connecting with other adoptees and sharing experiences can also help an adoptee feel less alone and discover ways that others have addressed feelings of guilt. For example, talking about what challenges, difficulties, and joys you have had.

3. For myself, contemplating these thoughts and feelings in prayer helped me to face them rather than to suppress them. When they became overwhelming at times, I was able to surrender them to God and place my trust in His divine plan. It was through prayer that I was led back to China and to the next response, service.

4. Service of others can help them focus their time and talents towards helping those in need, whether an adoptee chooses to return or not. Like myself, some desire to do this in their birth countries. Others find just as much fulfillment serving in their home country. Or both. Regardless, service will help the adoptee learn about human dignity; both theirs and that of others.

These suggestions are directed towards adolescent and adult adoptees. Feelings of guilt are different for children. To help a child who is experiencing feelings of guilt, parents can and should talk with their child if and when they are ready, and praise them when they do share their feelings with you.

Reassuring your child that their feelings are normal can be extremely helpful for a child. Don’t allow a child to believe that a traumatic event or whatever prompted their feelings of guilt was their fault. Again, professional help is often effective in helping adoptees of all ages to process many common feelings that they have.

Molly Schmiesing was adopted from Wuhan, China when she was 9 months old by an American couple from Cleveland, Ohio. She am currently living in Bei Jing with her husband Michael. You can read more on her blog, Finding China.

Love hearing your wisdom! As an adoptee who didn’t know I was adopted till my early 20s..much you say applies to even those of us who weren’t adopted into a brand new country and culture. I had so many questions and little answers. I felt different all my life. I felt different then my siblings, wondered why I seemed to be picked on by some of those siblings. Now I know most of my siblings didn’t understand me because I was the only one with my history in the family. Many conflicts ensued because of these differences as well and I always felt like I tried hard to fit and couldn’t. I feel this is why I strongly love that my kids from China will share their culture and their same special need with a sibling. I love kids so adding more then one from the same culture seemed a great fit for all of us. My hope is they will find their authentic selves and know it’s ok to be who they are and learn they don’t need to people pleases. Thanks for the helpful info. 🙂

Thank you for this. I was adopted and I definitely have that feeling of “why me?” that I’ve been struggling. Do you have any ideas of thought patterns that felt better than “I need to work harder to deserve this life” that would be helpful? Because I’ve been reading about adoptee guilt and some websites say that you should give back to feel better about it, so I’ve really been trying to do that, but realized that it has been to an unhealthy level where I feel like if I’m not perfect that I don’t deserve the life I have. I know it’s not great, but I’m looking at how to improve this.