So, this month we are focusing on Medical Interventions and how you can best prepare for them. Our hope is to not only help you navigate these potentially rough waters, but for you and your child to come out with a more deeply-formed attachment on the other side.

*Note: I have no training in trauma. I simply have a few notches in my medical momma belt, and gently offer here what I’ve learned.

Many of us adoptive parents said yes to the adoption of almond eyed, precious ones with needs, and by doing so, stepped outside the familiar territory of parenting healthy little people. We did so willingly, though we had no idea what that would look like, or how it might feel.

What breaks our hearts the most is watching our kids endure the poking and testing and NG tubes and chemo infusions and enemas and casting and surgeries and invasive tests and blood transfusions and echocardiograms and sleep studies and catheterizing. And how could we have known how those blasted IV sticks would make us crumble?

But it is all needed. So we do it.

Our family is with you, as our small people have experienced hospital stays, surgeries and a whole host of corrective and life-saving medical procedures. This is our offering on how we prepare and endure.

Parents

The most essential advice is, for us the emotional mom and dad, to stay calm. It’s going to take some time on our knees, because for every procedure, we need peace and trust like a protective blanket. We’ve simply gotta grieve another time. It’s our most important gift to them. They sense our tension and respond.

Take turns being the comforting parent. There are often many people in a hospital room during hard moments. We try not to add to it by adding noise and distraction attempts. One parent voice at a time.

Don’t make assumptions about what kids understand. Do they understand that medical professionals are helpers that have to do uncomfortable things to make us better? Do they understand that their casts/bandages will eventually come off or that bleeding will stop?

Surrender your efforts to make it all better. Let God be the God of your child.

Leading Up to a Procedure or Hospitalization

We are open with our kids. On a level they can understand, we tell them what to expect. We do this in pieces, step by step, when needed. If anesthesia or sedation will happen, we might say, “The nurses will give you some medicine to make you snooze while they help your body. You won’t feel anything. When you wake up, it will be all over.”

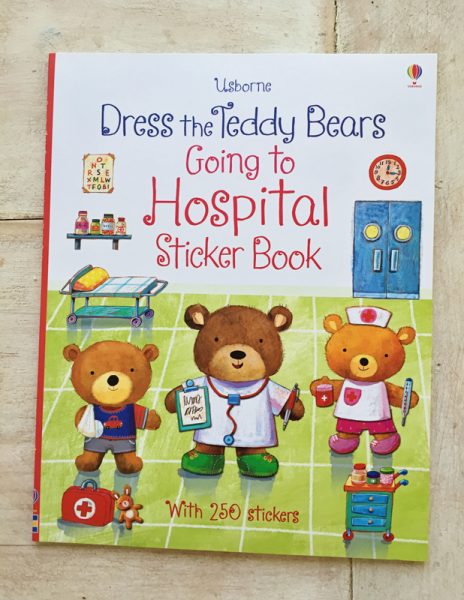

We purchase sticker books, such as Usborne’s Dress the Teddy Bears: Going to the Hospital Sticker Book and Going to the Hospital Sticker Book. We read books, such as Franklin Goes to the Hospital, The Berenstain Bears Hospital Friends and The Surgery Book for Kids.

Sticker and reading time helps us explain what nurses and doctors do, why they wear masks and use stethoscopes, what a hospital rooms look like, and what an IV machine does. We read these before, during, and after hospital stays.

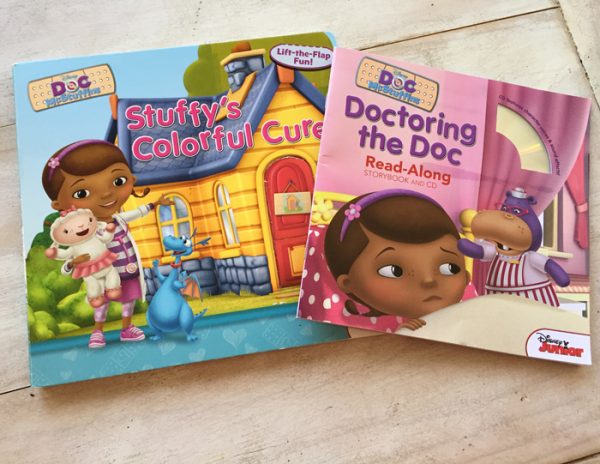

Dolls and toys expose kids to medical equipment in a fun, hands-on way, such as dolls in wheelchairs and Doc McStuffins doctor’s kits.

The International Children’s Ostomy Educational Foundation even offers ostomy dolls free of charge. We use these for conversational play.

Before a hospital stay, we let our kids shop for something fun for the hospital, such as crazy socks, a water bottle, slip on shoes that they can wear (once mobile) when walking the halls of the hospital, hair accessories or nail polish.

Promises

On the way to the hospital, we make some promises to look forward to. Then, in the hard moments, we can remind them of plans we made.

“You’ll get to see the big aquarium in the lobby.”

“There is a library and play room in this hospital. Should we check those out while you are here?”

“If you ever need it, let’s calm ourselves by doing our family hand shake. Or I can hold your hand and we can do big cheek breathes. I could rub your back too.”

“Mommy and daddy will buy you a balloon from the gift shop while you are with the doctors and nurses. You’ll see the balloon as soon as you see us. We’ll pick out a balloon for you from the gift shop. What kind should we look for?”

“All these people are here to help you. Should we draw them some of your cute pictures when you are finished?”

“After the nurse finishes, how about I snuggle in bed with you and watch a princess movie?”

Just Before Procedure

In the last moments before a procedure, we hold back those tears pooling in our eyes, remind them of our promises, pray, say we love them and distract.

Sing a song.

Make funny stuffed animals voices.

Talk about what flavor popsicle we should choose afterward.

During Procedures

If in the room during hard things (IVs, urodynamic tests, etc.), use a gentle and steady voice, even if they are screaming. We try to “ground” them by:

Holding their hands and questioning, “I’m holding your hand. Do you feel it?”

Ask them to squeeze your hand as hard as they can.

Touch their face and ask them, “Can I see your eyes? Can you see momma? I’m right here.”

Kiss their forehead or rub their hair. “I’m here. I’m here. Do you feel my kisses?”

Let Them Feel

When I was a new medical momma, while my in-pain child was sobbing during an IV/NG tube placement or invasive test, I found myself repeating, “You are OK. You are OK.” Somewhere along the line, I stopped saying this, and started offering permission to acknowledge hard things.

The truth is that what they are experiencing doesn’t feel OK. So, instead, I say, “Does this hurt, baby? I promise if you’ll be brave, it will be over very soon.”

These are gut-wrenching parenting moments. Unfortunately though, they are experiencing trauma. And processing pain is essential. We don’t want them to soldier through or hide their feelings. Crying is a healthy response. It’s alright if they aren’t “fine” or “okay”. We can’t take away hurt, but we can help them process through it.

After surgeries are over, we don’t just move on. They’ve experienced trauma, so we find ways to let them talk about what they experienced and how they felt. It’s not fun, but it’s helpful.

Special Requests

Be an advocate. Talk to doctors and nurses about your child’s past medical trauma and adoption attachment.

Ask to hold your child during breathing treatments or finger pricks.

Ask for permission to be with your child until they are on “loopy meds” or asleep. (Some hospitals allow this, some don’t, depending on the procedure. Just ask.)

Request to be in the recovery room when your child wakes up.

If a hospital doesn’t allow this, don’t panic. Most don’t. Kids are far more resilient than we imagine. We always tell our child later where we were and what we were doing while they were “asleep”. “We were in the waiting room waiting for a nurse to come and take us to see you. We prayed for you the whole time and went to buy you a balloon. We never left.”

Hospital Room

Provide familiar, sensory comforts: a favorite soft bear, fuzzy blanket, Play doh, something to squeeze or chew on. Rub your child’s back, listen to favorite tunes, or do a family handshake. Get in the hospital bed and hold them. On our last hospital stay, we used a diffuser with our daughter’s favorite scented oil.

Sometimes kids need to zone out. If your child is upset, it might be time for showing #769 of Frozen. If they are crying, turn it on and just gently ask questions and talk about the movie. Stick with it. They will eventually calm down when the room is calm again.

Other times, they need to not watch that 123rd movie. Turn on familiar tunes and read books. Color in a coloring book. Be the calm they need.

Tell them that after this is over, they’ll be going home and will soon start to feel better. Make no assumptions that they “get” what is happening.

Take full advantage of hospital play rooms, libraries, child life specialists, and art carts.

Find things to celebrate. “It was yucky to get your NG tube, but you did it! You are so very brave. Let’s make funny faces on SnapChat.”

These times are not fun. For every medical procedure we endure, I vote that we parents get badges or chocolate. We’re a strong bunch though, and we can do hard things.

In the end, most of the time that we wear a hospital ID sticker, we’re just doing our best, moment by moment, then hour by hour, until it’s day by day and we finally head home. We can’t expect ourselves to respond perfectly, but we can take some intentional steps about preparing our kids.

The good news is that these days will pass. Even if there is more medical fun to come, we’ll walk into hospitals and we’ll walk back out.

We’ll be the firm foundation for our little people, even if we are melting inside.

Because we love them, and it’s just what we do.

Courage, dear heart. – C.S. Lewis

Leave a Reply